This essay has been written to debunk dubious scholarship claims made by other historians about the meaning and origin of the words ‘Atheist’ and ‘Atheism’, resulting in what I describe as ‘junk Atheism’. These inaccurate claims have unfortunately become ubiquitous in popular media produced about Atheism over the past several decades, threatening to obscure the legitimate history of Atheism as a distinct and specific modern ideological movement philosophically rooted in scientific skepticism. This dubious information about Atheism has, unfortunately, been successful at gaslighting many self-identifying Atheists into believing these false claims, which necessitates the writing of this lengthy essay with evidence to debunk the ‘junk Atheism’ misinformation.

Introduction

There is a significant amount of confusion regarding the origin and meaning of the word Atheist in English that is both polluting online dictionaries and plaguing academic scholarship on the topic. A persistent misunderstanding arises from the conflation of the ancient Greek term ‘atheos’ (ἄθεος) with the modern English word ‘Atheist’. While these words may appear similar, their meanings, connotations and historical usages differ significantly. Christian apologists, historians and even some self-identifying Atheist scholars have frequently misrepresented the relationship between these terms by suggesting that Atheism has existed since antiquity. However, as this essay will demonstrate, the application of the term ‘atheos’ in ancient texts reveals that word held a very different meaning than the way ‘Atheist’ is used today as a modern self-identification. This is also because, contrary to claims made by the same dubious scholars, the Atheism intellectual movement is a unique concept which emerged only during the European Enlightenment era alongside the development of Empirical science and secular philosophies related to this Atheist intellectual movement. It has no precedence before this point in history.

A popular but erroneous claim is that the ancient Greek word ‘atheos’ possessed a literal meaning of ‘no gods’ and therefore the modern word ‘Atheist’ has this same meaning. In actuality there is no archeological evidence to suggest the word ‘atheos’ was ever used against a person who lacked belief in deities; instead the evidence shows the word was exclusively used as a slur against people who had different theistic religious views, often concerning the nature of the same deity the insulter believed in. The word was synonymous with the English word ‘heretic’. This is also not how the word ‘Atheist’ is used nor how it has been used since the development of the modern Atheist movement in the 18th century, as this essay will thoroughly detail. Ancient Greek ‘atheos’ and its derived words are, like so many words, misnomers whose practical meaning was not based in its literal meaning, the same way in which modern English speakers do not consider firemen to be men made of fire, a light-year is a measure of distance and not time, tin cans are made of steel and so on.

There are also those who repeat a popular platitude that to be an Atheist is some kind of ‘natural state’ free of all religious beliefs, but as so many platitudes are, this is wrong. Atheism does not mean ignorance of the concept of a god. It means disbelief of gods. Disbelief is a reactive state, not a passive one. You have to first hear someone claim a god exists in order to reject that claim, and in order to reject all claims anyone makes of a god existing the Atheist person needs a very specific thought process — a specific ideology based in naturalism philosophy.

As such, all claims that the ancient Greek word ‘atheos’ is the same word as modern ‘Atheist’, are unfounded. These claims violate the logic of language, and fundamental rules of logic such as the Law of Identity and the Law of Excluded Middle. The ancient Greek word ‘atheos’ does not hold the same meaning as the modern English word ‘Atheist’ does because atheos was not used the same way to describe the same kind of person as the modern word ‘Atheist’ does. The true etymology of these words, reviewing the actual history of the development of modern Atheism, demonstrates this conclusion.

Addressing Common Misconceptions about Atheism Lacking “Beliefs”

While there are many people both within and outside of the Atheism community who frequently claim Atheism to merely be a descriptive definition for a person who lacks belief in deities, in actual practice Atheism is inherently normative because it requires the adoption of an ethical position on the moral value of truth in order for a person to identify as an Atheist at all. This is obvious to anyone who scrutinizes how a person goes about identifying as an Atheist; while an Atheist may cite descriptive statements for rejecting the superstitious claims other people make of deities existing (most commonly by citing Empirical Science) the motive for the Atheist to decide it is correct to reject the meritless claims is a normative position on truth as a moral good; that is to say, the Atheist has a belief that they should not believe things that cannot be demonstrated to be true using rational reasoning. In short, Atheists do not reject other people’s claims about deities solely because there is no evidence for these deities existing but also because the Atheist has adopted a normative ethical view of truth as a supreme moral principle to justify why the Atheist should not believe in deities. It is due to this allegiance to truth that Atheists reject superstitious claims about deities existing. Consequently the claim that Atheism has nothing to do with ethics nor that it professes any moral position is a false one, as Atheism requires a person to adopt the life stance that truth is a moral good in order to justify why it is correct to reject other people’s claims of deities existing when there is no evidence for that existence.

To be clear, it is possible for a person to accept there is no rational reason to believe in a deity and yet decide to believe in that deity anyway. Indeed, this is what the vast majority of superstitious people do. What makes the Atheist different from the superstitious is not only knowing that there is no credible evidence for a belief in existence of deities, but this information combined with a normative view on the moral supremacy of truth. The Atheist rejects superstitions not just because these ideas are without merit, but principally because the ideas have no merit there then is no rational reason to think of them as true. That the Atheist is inclined to adopt only those beliefs that can be demonstrated to be aligned with reality is the most essential quality of Atheism, as this is the singular difference that separates an Atheist from other groups of superstitious people who are aware their superstitious beliefs are irrational yet decide to have “faith” that they are true anyway. The only thing that prevents an Atheist from also deciding to have “faith” is that the Atheist has the normative view that logic and science are the best means to determine what is true, and this view is what prevents the Atheist from disregarding the lack of credible evidence in the way the “faithful” superstitious person does.

Therefore, if someone who claims to be Atheist rejects belief in deities using reason on the basis those beliefs are not likely to be true but simultaneously embraces equally irrational ideologies as beliefs in deities as true, that person is not upholding the rational basis of Atheism, and therefore cannot maintain rigor in their beliefs structure. Their Atheism is at odds with their other ideological adoptions, and undermines the integrity of their Atheism. So Atheism is more than just a position on whether deities exist or not, because there are other ideological requirements a person must meet in order to conclude that believing in deities is wrong behavior.

(Those versed in philosophy may point out that Atheists without any further justifications for why truth should be viewed as morally good are at risk of engaging in a naturalistic fallacy. This is why Atheist philosophy requires additional justifications to defend why truth is a moral principle in order to be a coherent, well structured philosophy. I have developed these justifications in my Chivalric Humanism writings, which I have touched upon in other essays on Atheism Daily, such as my rebuttal to former Atheists who make a utility argument to justify so-called “cultural Christianity“. But other Atheist writers have also discussed moral justifications for truth in their own writings. I am not going to cover all of these different ethical frameworks that can be tacked onto Atheism to provide a rational justification for truth as moral good. In the previous paragraphs I have only pointed out what is minimally required in core beliefs in order for someone to meet the universally recognized definition of Atheism as “disbelief in deities”.)

Atheism is, therefore, an expressly intellectual movement that promotes truth as a moral good, which is why Atheists reject superstitious ideas that others claim about gods existing. Without this inherent claim about the supremacy of truth as moral then it would be viewed by Atheists as morally acceptable for religious leaders to knowingly promote lies about gods existing to guile others into service to them. Yet in actual fact, Atheists ubiquitously criticize religious leaders for spreading false perceptions of reality to their flocks on the basis that they are lying to manipulate others. This means truth is essential for Atheism as an ideology, and despite protests, Atheism of course is an ideology: Atheism philosophically requires a life stance that people should not believe gods exist, because those gods cannot be demonstrated to be real using rational reasoning. This is of course why New Atheism took it a step further with the claim that because the superstitious promotion of belief in deities leads people away from reality that Atheists therefore should actively challenge the promotion of these superstitious ideas.

Yet, it is often said as a sort of mantra by even by popular Atheist influencers that Atheism is not any kind of ideology or morality, claiming it is merely a lack of belief in gods. The reason this claim should be disregarded as a commonly repeated misconception is that if you actually assess the Atheism movement as a philosophical one, as I have done in the prior paragraphs, it is clear that Atheists are not merely people who lack belief in gods, but instead actively reject other people’s claims that gods exist. Atheists are not people who are ignorant about the idea of a deity, as if they just don’t know what the concept of a god is. Instead Atheists are people who do know what the concept of a god is and decide to specifically reject a belief in those gods. This rejection is not done because the Atheist believes in a different god but instead because the Atheist finds faults of reasoning in the claims other people make of any god existing. And it’s not a one-off case; the Atheist rejects ALL claims made by ALL people of deities existing, using the same epistemic reasonings. Therefore, there is an unsaid pre-requisite for the Atheist to have epistemic integrity in application of reasoning to these claims in order for one to meet the definition of Atheist. This is why Atheism is not just a descriptive definition as claimed by those who cite dictionary fallacies; there is a specific philosophical framework that Atheism entails. Atheism then, properly understood in full context of the intellectual movement underpinning it, is not just disbelief, but also requires a personal allegiance to reason as the highest standard for forming beliefs about reality in order to justify the disbelief.

Non-Atheists Who Seek to to Infiltrate Atheist Spaces by Feigning Secularism

As a consequence of commonplace misrepresentation of the meaning and origins of the word ‘Atheist’, in recent years there has also emerged a trend of pseudo-Atheists who try to use the definition of Atheism solely as “disbelief in deities” without embracing the broader scientific skepticism that is necessary to have this disbelief in the first place. This is a problematic historical revisionism that threatens to dilute the meaning of the word ‘Atheism’ from its use as the identifying label for a specific intellectual movement with scientific skepticism as its ideological basis, to instead include people as ‘Atheists’ who have absolutely nothing in common with genuine Atheism, such as people who hold superstitious beliefs in things such as reincarnation, ghosts and astrology that may not directly involve the worship of a deity but rely on the the same irrational reasonings that beliefs in deities also employ.

In fact, attempting to fold these irregular religious ideas under the banner of Atheism creates inherent contradictions, as it is logically incoherent to reject a belief in deities due to a lack of credible evidence while simultaneously accepting a belief in other equally superstitious ideas that also lack credible evidence.

Thus, as a result of misleading definitions promoted by dictionaries and dubious scholarship on the topic, over the past few decades there has emerged concerted efforts by groups of astrologists, spiritualists and even so-called ‘secular Buddhists’ (a disingenuous labeling considering Buddhism’s core foundational tenets are unavoidably tied to a belief in souls, reincarnation and higher planes of existences where deities reside) to co-opt the term ‘Atheist’ for themselves, when in fact the superstitious beliefs of these infiltrating groups are also discredited by the very same skepticism that Atheists use to discredit religious such as Christianity. After all, it is expressly the superstitious ideas about deities that result in their belief among the religious and it is specifically the debunking of these superstitious ideas that results in Atheist disbelief.

After scrutiny of their statements and actions, it is clear these efforts by non-Atheists to interject themselves into the Atheism movement is designed to co-opt its branding and organization structures for their own purposes. As a high profile example, the former Atheist organization Atheist Alliance of America (AAoA) was usurped in 2016 by Mark W. Gura who rebranded it as Secular Help, an organization that sells expensive “secular Buddhism” meditation retreat vacations and online spiritual counseling services. Upon close scrutiny the Buddhism promoted by Gura is not actually secular at all but instead Vipassana Buddhism that promotes a cosmology of superstitious ideas regarding reincarnation and souls. These superstitious ideas are often downplayed to new converts to Vipassana for fear of scaring them away, but like any superstitious religion they become more prominent the deeper a person goes into Vipassana literature.

This co-opting of unique Atheist identity should be adamantly rejected by genuine Atheists in order to preserve the intellectual consistency of Atheism as an ideological movement based in scientific skepticism and ensure Atheism continues to flourish as such in the future without its usurpation by people who objectively do not share the same intellectual framework genuine Atheists do. That the Atheism movement is likely to collapse if it is permitted to expand its definition to include these superstitious people is not hyperbole -– superstitiously religious people far outnumber Atheists who reject beliefs in supernatural things. Atheism as a movement therefore cannot endure if its organizations and communities are seized by “Atheist pretenders” whose core beliefs, while perhaps not those of mainstream religions as in the case of fortune telling, are still as equally nonsensical as other mainstream religious beliefs in deities such as Jesus and the Buddha.

In short, scientific skeptics who reject a belief in gods due to a lack of credible evidence have nothing intellectually in common with people who believe in reincarnation, astrology horoscope, tarot card readings, ghosts and other superstitious ideas that lack scientific rigor. Therefore the latter group of superstitious people cannot be true Atheists, as Atheism is historically linked to the first group, who are in conflict with the second group. This conflict in worldviews is the entire reason why Atheism became a movement to start with.

(As a side note, I have had this argument with many people who erroneously try to claim what I have just said is a No Scotsman fallacy; the reason it is not, is because a No True Scotsman fallacy occurs when someone moves the goalposts of a definition arbitrarily in order to protect a group identity from counterexamples. As I never move the goal posts of what Atheism means — a disbelief in deities — but only point out what behavior is necessary for a person to meet the definition, it is not a No True Scotsman Fallacy. Atheism has necessary properties in order to be a rational worldview and as such, it must adhere to certain rules to create that worldview. One of those properties is a belief that science has disproved the existence of the supernatural. The philosophy of Atheism thus requires it possesses a normative, epistemologically grounded definition not merely a descriptive one.)

The more accurate label for belief systems that do not worship a deity but contain other similar superstitious ideas is the academic term Non-Theism used in the field of Religious Studies. While Atheism is a form of Non-Theism, not all forms of Non-Theism are Atheistic. This is because the historical development of Atheism as a specific intellectual movement is intertwined with the development of the Scientific method and resulting philosophies that emerged from it, namely Empiricism. There are specific claims about the nature of reality and the best way to determine what is real that are fundamental to Atheism for this reason, and it is not a vague merely descriptive label the way that Non-Theism is.

Addressing Disreputable Information about Atheism on Popular Websites such as Wikipedia

Contrary to what is claimed by unreliable sources who do not possess a genuine knowledge of the historical development of the Atheism intellectual movement, the idea of Atheism has no precedence in cultures that predate the Scientific revolution nor which are influenced by it. Here I am specifically disputing the claims people have made of Atheism appearing in historical Indian religions such as Buddhism, Samkhya and so forth. These belief systems are erroneously included in the Wikipedia article on Atheism as part of its history section and the reason these claims are objectively false ones is because these religions all involve a belief in superstitious ideas, with cosmologies that contain higher planes of existence where deities reside. These religions also have absolutely nothing to do with the chronological order of events which led to the development of the philosophical school of Empiricism in the West. Furthermore, the article mentions Charvaka, whose Wikipedia article contains numerous dubious claims considering there is no historical evidence that Charvaka was a structured organized school of ancient Indian philosophy — it has no texts or philosophers. Charvaka was instead a label for people who disagreed with more mainstream Hindu religions using materialist arguments, and much like the term ‘Atheos’ in ancient Greek writing, is a term no one identified as, but instead a label that religious opponents used against their detractors. Claims that Charvaka was some kind of well organized school of philosophy are historical revisionism and not supported by the archeological record.

I am left with the conclusion that the only reason these religions appear in the Wikipedia Atheism article is because powerful wiki editors refuse to remove the material despite the objectively false claims about their role in the development of Atheism; as I said earlier, there is an active organized effort by non-Atheist groups to infiltrate the Atheist movement and co-opt it for their own purposes. There are many people who view Atheists as having no core beliefs and therefore easy prey for recruitment into their new religious movements. Part of this infiltration is the spread of dishonest historical revisionism pretending these religions are part of the history of Atheism when objectively they are not.

To put simply, when the term Atheism is diluted to mean all forms of Non-Theism, it leaves that group of people who have historically used the name ‘Atheist’ as a self-label specifically to indicate their science-based rejection of all supernatural beliefs without a clear, unique label for their worldview and communities. While this confusion may benefit people of other religious beliefs seeking to spread misinformation about Atheism so as to undermine its credibility as a competing intellectual movement, transforming the term ‘Atheism’ from a specific label into a vague catchall term for a number of entirely different belief systems does not benefit the people who have historically identified as Atheists.

To be clear: contrary to what is popularly claimed in many dictionaries, the word ‘Atheist’ does not possess the literal meaning, ‘lack of belief in gods’. This claim is frequently built by suggesting the word Atheist derives directly from ‘atheos’, an ancient Greek word having that literal meaning but which in actual practice was used by ancient Greeks to insult people who did not believe in mainstream religions of the ancient Greek city-states. The word ‘atheos’ was not used in a literal sense, as present day pseudo-historians often claim. Instead the actual way the word ‘atheos’ was used, based on the surviving historical records mentioning the word, was exclusively as a misnomer – that is, atheos was not actually used to describe people who rejected all religious belief in deities. Atheos was instead a derogatory term for those who did possess religious beliefs in deities, but those beliefs were not the same as the person accusing the other of being an atheos. There is no historical evidence of anyone self identified as an atheos in the Ancient Greek world. The term was equivalent to the English word ‘heathen’ or ‘heretic’ as used today by different people belonging to different factions of the same religion, and primarily lobbied against people who had slightly different religious ideas on deities.

For example, Socrates was famously accused of being atheos for having different beliefs about the state deities of Athens. This accusation stemmed from Socrates’ rhetorical debates where he suggested that deities could not be ‘human-like’ and suffer from human faults but instead should be perfect supreme beings, which clashed with the mainstream Athenian view of deities.

Similarly, Epicurus is often falsely claimed to be the ‘First Atheist’ by promoters of dubious scholarship when in fact there is nothing in the historical records to suggest this and in fact, the Epicurus paradox named for him describes his actual recorded viewpoint, which is that deities existed but did not involve themselves with human affairs.

There is an unfortunate tendency for scholars to treat any form of historical religious skepticism as Atheism, when in fact all religious skepticism is not Atheism.

However it is also important to understand we have no primary sources for what ancient Greek thinkers such as Socrates and Epicurus truly taught; everything we know about them come from secondary sources and those surviving accounts are copies made hundreds of years after these people had died. Our knowledge of the truth of what these ancient Greek philosophers believed is therefore very limited, and what we refer to as the teachings of Socrates or Epicurus and the others, all stem from these copies of copies – not any genuinely primary sources. This is another reason why it is incorrect for people to claim modern Atheism is the same concept as atheos, as the idea of atheos may not even be a real ancient Greek thing but a later invention. The word is rarely used in any surviving ancient Greek sources and instead primarily used by later Roman commentators such as Cicero, but even in this case what survives of Cicero’s writings are themselves copies of copies made long after he died. The important thing here is that we know two essential facts; 1) the word atheos was never used by ancient writers the way the modern word Atheist is used and 2) therefore it is not the same idea.

Refuting the Historical Revisionism that Claims Atheism Has Identical Meaning to Older, Different Words

Furthermore, as latter sections of this essay will demonstrate, the historical record clearly shows that the word ‘Atheist’ actually does not directly derive from the word atheos, but instead from several other words originating in languages that include French, Italian and German. While these words were influenced by the older Greek word ‘atheos’, and originally shared its meaning in the sense that they were synonymous with the word ‘heretic’, by the time that the word ‘Atheist’ developed in modern English with its use of the modern English IST suffix, the meaning had shifted substantially in popular usage to exclusively mean those who reject a belief in deities because they have a scientific skeptical worldview– and this is an important detail which at present the dictionaries with entries about Atheism do not recognize due to poor scholarship on the topic when writing these dictionaries.

Examples of this mistake in defining the word Atheist can be found in numerous sources, including the Online Etymology Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Dictionary (which also lists its synonyms as ‘infidel’, ‘pagan’, ‘heathen’ and ‘miscreant) and every other online dictionary I’ve came across. The mistake has even made its way onto the page copy for the websites of American Atheists and the aforementioned Wikipedia entry for Atheism.

An important issue that contributes to this misunderstanding is the lack of attention paid by these scholars to the development of the -IST suffix in English. The suffix “-ist” is a feature of Late Modern English, primarily emerging in the 18th and 19th centuries to indicate a person associated with a particular ideology or profession. English words such as abolitionist, capitalist and socialist all emerged in this period as well.

As the word ‘Atheist’ follows this same linguistic pattern, it is improbable that it existed in its modern form before the late 18th century, even if related terms such as atheos, atheus or Atheiste existed in other languages. There is certainly no evidence of such a word with the modern meaning existing before the late 18th century when older historical documents which are claimed to contain the word ‘Atheist’ are actually read.

Thus, any claim that the modern word ‘Atheist’ existed before the 18th century is an anachronism, as the very linguistic structure of the word indicates it is a modern English word and the way the word is used by contemporary speakers of English is radically different than these other previous words that are synonymous with ‘heretic’. The actual modern spelling ‘Atheist’ could also not have been used prior to the widespread typographical transition from the English word Atheiſt to Atheist in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as I will explore in detail later in this essay.

Therefore the crux of my claim in this essay is this: In its actual usage by contemporary English speakers, ‘Atheist’ and ‘Atheism’ are both terms that describe a pre-packaged ideology; one that must contain a naturalistic science-based worldview as the reason for the rejection of belief in deities, as well as all other supernatural things. Contrary to what is often claimed in dictionaries and encyclopedias, the word ‘Atheist’ does not share meaning with its direct predecessor, the Early Modern English word ‘Atheiſt’, which was a term that had the legal meaning of committing blasphemy by denying the existence of the god of the state-religion, but was more commonly used as an insult during the European Reformation period of the 16th and 17th period. Catholics and factions of Protestants debated each other primarily using ad hominem attacks on the other’s character, and threw the word Atheiſt around quite frequently at their opponents; almost never to actually imply that the criticized person didn’t believe in the Christian god, but instead to accuse them of believing in doctrines the critic viewed as heretical due to their interpretation of Biblical scriptures. The word Atheiſt was therefore almost never popularly used to mean someone who literally did not believe in a god, but instead someone who disagreed with how to worship the Christian god. Atheiſt was also not used as a self-identifier during this time period; it was expressly used as a slur.

This is, obviously, not how the word Atheist is used in contemporary English. Contemporary Catholics and Protestants do not run around accusing the other of being Atheists. While it certainly derives from Atheiſt, the word Atheist has its own unique meaning and it has held that meaning since the dropping of the Long S character ſ in English during the mid to late 19th century; a time period which coincides with the popularization of naturalistic science-based worldviews that shun belief in superstitious ideas. The word Atheist became used as a self-identifier to describe this science based worldview, and that is why different factions of Christians no longer use the term to insult their Christian rivals as they had once done with its predecessor Atheiſt.

Refuting Christian Apologetic Writers Who Gaslight Readers About the History of Atheism

Despite these historical facts about the development and usage of the word Atheist differing from similar sounding words used in the past, Christian apologetic writers throughout the 20th century have continued to treat the word ‘Atheist’ as if it still has the same meaning as Atheiſt, and to even construe it with other words like the ancient Greek atheos, often by misrepresenting the definition of these more ancient terms to create the illusion of a link to modern Atheism. These apologetic writers have produced many books claiming to trace the history of Atheism and/or that criticize Atheism, using this strawman definition for the word in order to justify their attacks upon modern Atheism as an ideological movement.

A recent example of this strawmanning is Tim Whitmarsh’s 2015 book Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World where he claims that Atheism existed as an ideological movement in the ancient Mediterranean world and he references ancient Greek figures such as Epicurus as an example. In his book he claims Atheism is a tradition that is comparable in its antiquity to Judaism and is older than Christianity or Islam. To justify this claim, he defines all forms of religious skepticism throughout history as Atheist, even if the skeptic did in fact have beliefs in deities.

Whitmarsh’s claims of Atheism as a long tradition, clearly not scrutinized beyond the surface level, have allowed him to be platformed by various Atheist organizations, such as a April 24, 2017 UNE Center for Global Humanities event where he delivered a lecture titled, How to Be an Atheist — The Ancient Greek Way and a video on the Humanists UK YouTube channel titled, Atheists in the ancient world | Tim Whitmarsh on humanist history. However, closer inspection of his actual statements reveals he is nothing more than yet another Christian apologetic gaslighter, as his work is also platformed on Christian apologetic websites such as a January 28th, 2016 article, ‘A frustrating quest to find history’s first atheists’ published on The Catholic Herald where he is quoted as saying his book does not, “prove the truth (or indeed falsehood) of atheism as a philosophical position”. In his book, Whitmarsh claims that the perception of Atheism as a triumph of science over religion to be a “modernist vanity” and a form of “delusional self-congratulation”, and that it is a myth that “21st-century middle-class Westerners have been the only people throughout history capable of finding problems with religion”.

In a June 13, 2017 interview he did with Scott Douglas Jacobsen on Jacobsen’s Medium blog, Whitman actually admits his presentation of the meaning of Atheism differs from what it means in the modern sense. To quote him,

“I think if you ask most people, they would say atheism is a product of the modern West. It has its roots in the European Enlightenment, in the rise of science and the Industrial Revolution, and in the formation of modern secular democracies like the United States. There is much truth to this picture of course: atheism as we understand it today is a modern phenomenon. But it’s that qualification ‘as we understand it today’ that is critical. Why should we understand atheism only from a modern perspective? The words atheos (‘atheist’) and atheotēs (‘atheism’) are over 2000 years old. The job of someone like myself, a classicist, is to try to change the angle of vision, and to jolt people out of their assumptions that their own categories of analysis are the only ones possible.”

I protest this. In actuality, it is not the job of a Classicist historian to re-interpret modern English words to have new meaning based on significantly older words that were used in completely different ways. Rather it is the job of a Classicist historian to do the same thing every historian should be doing; accurately presenting history in its proper context so that people do not misunderstand past events, such as by construing atheos to have the same meaning as Atheist when they are, in fact, entirely different words used in a very different way. They should not be promoting anachronist viewpoints of history and thus engaging in unmerited historical revisionism.

So clearly, what we can deduce by analyzing Whitmarsh’ statements about his book and why he wrote it, is because Whitmarsh views Atheism as a falsehood and he is disingenuously representing himself to Atheist organizations as a legitimate scholar to gaslight them into embracing his pseudo-history. This deception has been successful because these organizations are, tragically, presently steered by people who lack a detailed knowledge about Atheism’s history. They do not understand Whitmarsh’s work claiming Atheism to be an ancient tradition is engineered to discredit the Atheism movement by convincing others of a strawman argument definition for Atheism that apologetics find easier to attack, as it separates Atheism from the naturalistic science-based worldview that underpins its credibility as an ideological movement. If you convince others to remove this element from Atheism then Christian apologetics can more readily debate Atheists by disarming them of that which is employed to criticize Christianity and which the Christian apologist has no ability to defend against — modern science.

The Promotion of “Junk Atheism” by Non-Atheist Authors

As a sneaky insidious apologetic, Whitmarsh is not unique in this behavior; he is only a recent example of a tradition Christian apologetics have been practicing throughout the 20th century, most notably the Catholic Jacques Maritain in his 1952 book The Range of Reason where he claimed to invent “categories of Atheists” such as ‘Absolute, Positivist, Practical, Pseudo and Real Atheists”, which later became further codified by Antony Flew in his 1976 The Presumption of Atheism, as “Weak and Strong Atheism”. Flew masqueraded for decades as an Atheist when in fact he was a Deist, only admitting such in 2004 after coming under pressure once his views were more closely scrutinized, and which he clarified in a October 10, 2004 Secular Web statement in which he admitted that his Deist beliefs were aligned with the arguments he made in The Presumption of Atheism. In the 2010s another supposed ‘Atheist’, Michael Ruse, co-authored The Oxford Handbook of Atheism with Catholic theologian Stephen Bullivant and published essays on Christian apologetic websites criticizing New Atheism, which of course is not the behavior you would expect of a genuine Atheist. Ruse was instead a Darwinianist seeking to marry the facts of evolutionary theory with Christian religious belief, and he gaslit people about this by feigning Atheism by embracing the kind of strawman redefinitions invented by the apologist Jacques Maritain and further perpetrated by Flew.

Maritain and Flew’s ideas about Atheism having categories have, in my opinion, greatly damaged the Atheism movement during the 20th and early 21st century as many Atheists have accepted these categories with little scrutiny about them, resulting in what I refer to as ‘junk Atheism’. This ‘junk Atheism writing’ has successfully convinced many in the Atheist community to downplay the inherent ideological positions of a person possessing an Atheistic worldview to make it seem like Atheism is merely an absence of belief in deities, despite that no one they knew in the Atheism community is ignorant about what a deity is supposed to be. That there could exist this idea of “weak Atheism”, which they defined as a person who lacked a belief in deities but didn’t believe deities could not exist. The existence of ‘Weak Atheists’ is justified by these adopters of Flew’s rhetoric through the claim that there exist some isolated peoples in remote places who have never heard of the concept of deities before, even though no one can identify any real group of isolated people like this. Regardless of whether such a mythical group of people really exist at all, ignorance about what the idea of deity is, is not Atheism, because a person who is ignorant of what a deity is just a type of non-theist. Non-theism is a broad umbrella category that Atheism as a modern intellectual movement falls underneath.

The problem with the claims of “positive” and “negative”, “weak” and “strong” Atheism actually existing as dedicated beliefs within the Atheist movement is that the weak and negative versions are not real beliefs anyone actually has within the Atheist movement; these labels are clearly nonsensical when a person epistemically analyzes the actual beliefs of Atheist people. In order for a person to even identify as an Atheist they have to first know what a deity is and actively reject a belief in all deities, making the criteria of “weak Atheism” impossible for anyone who identifies as an Atheist to realistically meet. Therefore the rhetoric around concepts like “negative Atheism” and “weak Atheism” simply do not withstand scrutiny when logically critiqued and therefore, these things cannot actually exist as real ideological positions within the modern Atheist movement. This is why I call this kind of rhetoric “junk Atheism” — the rhetoric sounds good on paper, but bears no actual resemblance to what real Atheist people believe and how they behave. Of course, the terms were never actually meant to represent real positions Atheists have, because they were ideas invented by Christian apologetics seeking to create strawmen they find easier to attack since they cannot actually refute real Atheist positions.

Again, these are all examples of what are very clearly Christian apologetics worming their way into Atheist communities seeking to redefine Atheism in ways that undermine it as an intellectual movement with a consistent definition. Whitmarsh is only the latest of these sneaky apologists to attempt this and find success.

Whitmarsh is, at present, Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge and has held that position since April 1, 2023. I am singling out his work as an example of many such similar books because this is a case that represents the issue this essay is designed to address, that poor and often purposely disingenuous Christian apologetic authors have abused their academic positions to promote blatant lies about Atheism that have become popularly accepted as truth by unsuspecting readers who are not themselves very familiar with the topic. This has even confused many people into identifying themselves as ‘Atheists’ despite the fact they hold superstitious beliefs in things like reincarnation, astrology horoscopes or even the existence of ghosts – all things that are actually impossible for an Atheist to believe in given that Atheism is exclusively a naturalistic science-based movement that rejects all superstitious things.

Whitmarsh’s book is a completely disingenuous one written by yet another Christian apologetic who, unable to refute the argument against the existence of the god he believes in, has embraced a strawman definition of Atheism he finds easier to discredit. The mere suggestion that the ancient Greek word atheos carries the same meaning as the modern English Atheist / Atheism is built on a fraudulent depiction of history and linguistics. In actual fact, atheos was a slur used by critics against anyone who rejected the more mainstream Greek religious viewpoints — and yes, there were indeed mainstream viewpoints, contrary to what he claims in his book. The Greek city-states, much like every other culture of the time period, penalized those who denied the existence of their deities. Polytheism did not mean there were no established state deities that all were required to pay tribute to. It’s well established that such state religions did in fact exist. Famously, as recorded in both the Apology of Socrates by Plato and the Apology of Socrates to the Jury by Xenophon of Athens, in 399 BCE the Greek philosopher Socrates was condemned to death by authorities on the charge that he disrespected the gods of Athens. But more importantly, Whitmarsh asserts figures such as Epicurus were called “Atheists” by construing the meaning of the modern English word ‘Atheist’ with that of ancient Greek atheos, when in fact these are very different words used in a different way to mean different kinds of people.

The most crazy thing here is that several times in his book Whitmarsh even admits these ancient people did not use atheos the way that modern English Atheist is used, but then carries on with his claim that the two words can mean identical things. This contradiction exposes his deception – he realizes his core claim is wrong, and yet proceeds to continue claiming it anyway.

The publisher of Whitmarsh’s book should be embarrassed to have released this book, and Cambridge should be embarrassed to have employed him as a professor of ancient history. No one should consider his book to be a credible work on the history of Atheism, as it is abundantly clear the author has allowed his personal religious beliefs and desire to discredit Atheism to taint his interpretations of ancient Greek society and create pseudo-history that ignores the actual historical development of the modern Atheism movement that is intertwined with modern Naturalism and Empiricism (modern science).

Simply put, Epicurus believed that deities existed and he was no Atheist. Ancient Greek beliefs did not resemble the modern Atheist worldview that is rooted in scientific skepticism, for the simple fact that modern science hadn’t developed yet. It’s only in the last few hundred years that ‘science’ has come to even be synonymous with naturalism, considering that until this time superstitious practices like alchemy and astrology fortune-telling were referred to as ‘science’. A scholar of European history ought to know that, especially one who is writing about the history of Atheism.

The foundations for modern science may originate to the ancient Greek world, but so do the foundations for Christianity as well. Just as it would be folly to suggest Plato and Aristotle were Christians merely because some of their ideas made their way into Christianity, it is just as erroneous to suggest the Ancient Greeks were Atheists merely because some of their ideas led to the development of Empiricism hundreds of years later. Likewise, just because Atheists endorse Empiricism to reject a belief in supernatural concepts like deities, it would be wrong to suggest everyone who is an Empiricist is an Atheist. Yet this is the kind of false reasoning Whitmarsh uses throughout his book to make the impossible claim that Atheism originated in the Ancient Greece world.

I could cite many other examples of this kind of pseudo-academic scholarship that is purposely misleading about the origins of Atheism. Many texts used as sources about Atheism, including dictionaries and historical references, erroneously claim that the term first appeared in the 16th century. These claims are often based on citations from works such as John Martiall’s A Replie to Mr. Calfhill’s Blasphemous Answer (1566), where the term ‘Atheist’, according to the authors of these sources, appeared in print for the first time. However, closer scrutiny of original facsimile copies of works such as this (which still exist in library and museum collections) reveals that the actual word used by these 16th century writers was “Atheiſt”, a word that features the archaic long S (ſ). This is a crucial distinction because Modern English did not fully emerge until the mid-to-late 18th century, and the shift from Atheiſt to Atheist occurred only after the long S character (ſ) was abandoned in English typography in the early 19th century. This change is significant as it also coincides with the change of meaning that the word Atheiſt took on from the 17th century onward.

The motivation for Christian apologists to gaslight people about the history of Atheism is easy to understand – apologists are seeking to justify their worldview through the discrediting of that which undermines it. The Atheist worldview about the existence of deities and supernatural events like miracles described in the Bible is not refutable and cannot be beaten in a formal debate simply because apologists have no credible evidence for the existence of their god, and the Bible has repeatedly been demonstrated to be a pseudo-historical collection of different stories that were written long after the events they describe. Now that modern societies such as the USA permit freedom of speech as a fundamental right of the citizen, the apologists cannot force compliance with the Christian worldview using state violence to silence critics as has historically been practiced. The only strategy the apologists are left with to employ against their critics is deception – the purposeful spreading of misinformation to gaslight others into believing a fabricated pseudo-history about Atheism and what it is. As part of this, they deny that Atheism is an intellectual movement founded in naturalism and Empiricism. By convincing others to view Atheism as separate from modern science it allows the Christian apologists to create strawman definitions of Atheism they find easier to criticize. This is why it is so important to identify this gaslighting and point out the fallacious claims made by Christian apologists, and even those who identify as Atheist who may have unknowingly adopted some of their ideas. Apologists’ pseudo-histories have insidiously spread into every dictionary definition about Atheism, and even widely cited works about Atheism that have been produced by Atheists, such as the Encyclopedia of Unbelief (1985) by Gordon Stein.

The time for this madness to end is upon us and this is the reason for why I have written this essay. Thus ends my lengthy introduction explaining the need for my research and now we can dig into the subject properly.

The Actual Origins of the Word “Atheist” in Early Modern English

The Earliest Uses of “Atheiſt” in English

The earliest known use of the word “Atheiſt” in English date back to the 16th century, during a period of intense religious conflict and political upheaval called the Reformation. One of the earliest confirmed instances appears in John Martiall’s 1566 work, A Replie to Mr. Calfhill’s Blasphemous Answer. Martiall, a Catholic polemicist, used the term “Atheiſt” as an insult against the Protestant Bishop James Calfhill, accusing him of being “litle better than an Atheiſt” for rejecting what Martiall believed was the true faith, Catholicism.

My citation for this claim is a facsimile of the original printing reproduced from a copy held in Library of York Minster. Page 162 clearly shows that the word is not ‘Atheist’ but Atheiſt. Pointing this out is necessary, as many dubious sources claim it is the earliest appearance of the word Atheist in English, when it is clearly not. Atheiſt in this context did not mean Atheist in the modern sense of someone who explicitly denies the existence of all gods. In Early Modern English, the term Atheiſt was frequently used as a pejorative accusation rather than a self-identification. To be called an “Atheiſt” in the 16th and 17th centuries was to be branded a dangerous heretic, an immoral libertine or an enemy of religious authority.

In 1571, just a few years after Martiall’s use of the word, the term appeared again in Arthur Golding’s translation of John Calvin’s Commentaries on the Psalms. In his epistle dedicatory, Golding wrote: “Ageine, the Atheiſtes, which say in their hartes there is no God…”

Here, Golding’s use of “Atheiſtes” (plural of Atheiſt) translates Calvin’s Latin remarks on Psalm 14:1 (“The fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God'”). However, much like Martiall, Golding did not use the term to describe people who rejected theism entirely but rather those who were considered morally corrupt, heretical, or rebellious against religious orthodoxy.

The primary function of the term “Atheiſt” in this period was to vilify opponents in religious and philosophical disputes, not to describe an actual group of self-identified Atheists who rejected a belief in the Christian god. No one openly claimed to be an Atheiſt, as doing so could lead to social ostracization, imprisonment, or execution. Instead, the word was hurled as a rhetorical attack in theological debates between Catholics and Protestants, and later between different Protestant sects.

By the 17th century, the word had become even more loaded, used to condemn skeptics, deists, and anyone who questioned the role of divine authority. The Jesuit priest François Garasse, for instance, in his 1623 polemical work La Doctrine Curieuse des Beaux Esprits, denounced libertines and skeptics as “Atheiſts”, portraying them as threats to both Christianity and societal order (page 4 of the facsimile of the original).

The Long S (ſ) Confusion and the Misattribution of Early Uses

A major source of confusion in the history of the word “Atheist” comes from typographical changes in English printing, specifically the use of the long S (ſ).

In Early Modern English (15th–18th centuries), the long S (ſ) was commonly used instead of the modern short ‘s’ in most positions within a word, except at the end of words or in capitalized form. This means that in original printed texts, the word “Atheiſt” appears with the long S, making it look similar to “Atheift” to modern readers.

Because of this typographical convention, many 19th- and 20th-century scholars misinterpreted early printed texts, mistakenly assuming that “Atheiſt” was the same as the modern word “Atheist”. This has led to widespread but incorrect claims that the word “Atheist” appeared in 16th-century texts in its modern spelling, when in fact, no such instances exist before the late 18th century.

The misinterpretation of the long S has been especially problematic in historical dictionaries and etymological studies. For example:

- The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) lists the first appearance of “Atheist” in 1571, citing Golding’s translation of Calvin. However, a closer inspection of original facsimile scans of the text shows that Golding actually wrote “Atheiſtes”, not “Atheists”.

- Similarly, John Martiall’s 1566 work has been frequently cited as the earliest recorded use of “Atheist”, but facsimiles of the original printing confirm that Martiall used “Atheiſt” with the long S (Martiall pg 162).

- Many 19th-century scholars, unfamiliar with Early Modern typographical conventions, mistakenly transcribed these texts using the short “s”, thereby introducing false claims that the word “Atheist” existed in its modern form centuries before it actually did.

This confusion persisted well into the 20th century, leading to widespread misinformation about the earliest appearances of the word. In reality, the transition from “Atheiſt” to “Atheist” did not occur until the mid 18th and early 19th centuries, when printers began abandoning the long S in favor of the short S.

The final transition to the modern spelling “Atheist” was solidified by the 1820s, after most printed English texts had standardized modern spelling conventions [Source: West, Andrew. “Rules for Long S.” *BabelStone*, 2006].

Thus, any claims that the specific word “Atheist” appeared in print before the mid-18th century are incorrect—they result from a typographical misunderstanding, not an actual historical usage of the word in its modern form.

Furthermore, by the time the long S (ſ) was dropped and ‘Atheist’ became the spelling, it exclusively meant someone who rejected a belief in gods and other supernatural things because of a science-centric worldview. Thomas Jefferson was famously accused of being an Atheist during his presidential run in 1800 for this very reason, because he rejected a belief in miracles and viewed the Bible as allegory. It would be more correct to call him a Deist though, but the point is the reason why he was accused of being an Atheist is because of his naturalistic views that rejected all superstitions, not just deities.

In fact, most of the Founding Fathers of the United States were citizen-scientists who embraced a naturalistic worldview. While many of them were Deists, they had skeptical views on religion and this is why freedom of religion was established as a right of all citizens in the USA. They championed government rule through reason, not dogma or superstition, and this is a defining moment in world history that created the conditions necessary for Atheism to emerge and flourish as an ideological movement throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Linguistic and Typographical Evolution of “Atheist”

Standardization of English Spelling and the Transition from “Atheiſt” to “Atheist”

The transformation of “Atheiſt” to “Atheist” was a direct consequence of the standardization of English spelling and typographical conventions in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Before this period, English spelling lacked uniformity, with considerable variation in how words were written across different texts and regions. The shift from “Atheiſt” to “Atheist” was not merely a minor typographical change but was part of a larger movement toward linguistic modernization, which sought to make English more readable and systematically structured.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the term “Atheiſt” was the standard spelling in printed texts. This was due to Early Modern English typographical conventions, which employed the long S (ſ) for any lowercase “s” that appeared at the beginning or in the middle of a word. Because of this, when scholars and readers today examine early printed works, they often mistakenly assume that “Atheiſt” was spelled “Atheist” in its modern form.

The misreading of historical texts due to the long S (ſ) usage has led to widespread misinformation regarding the earliest appearances of the modern spelling. For instance, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and other reference sources have mistakenly cited John Martiall’s A Replie to Mr. Calfhill’s Blasphemous Answer (1566) and Arthur Golding’s 1571 translation of John Calvin’s Commentaries on the Psalms as the earliest instances of “Atheist” in English. However, facsimile scans of these texts confirm that both Martiall and Golding actually used “Atheiſt” and “Atheiſtes,” respectively, employing the long S.

This orthographic tradition persisted well into the 18th century, with “Atheiſt” remaining the standard printed form. The eventual transition to the modern spelling “Atheist” was driven by the evolution of English typography and printing technology, particularly the gradual abandonment of the long S (ſ) in favor of the short “s.”

The Role of 18th-Century Printers

As mentioned previously, one of the key figures in the shift away from the long S (ſ) was John Bell (1745–1831), a British printer and typographer. Bell was among the first to completely eliminate the long S from his publications, setting a precedent that accelerated the adoption of the modern short “s” in English printing.

In 1785, Bell published an edition of Shakespeare’s plays, which was one of the first major works to omit the long S entirely. His British Theatre series (1791–1792), which included reprints of classic plays, solidified this typographical innovation, making his approach a model for other printers.

Bell’s work influenced a broader shift in English typography, leading to a gradual decline in the use of the long S in printed books and newspapers. By the 1790s, many English publishers had begun adopting the modern short “s” exclusively, though remnants of the long S still appeared in some texts.

The final phase of this typographical transition came in 1803, when The Times of London officially stopped using the long S in its publications. As one of the most influential newspapers of the era, The Times set a clear industry standard, marking the end of the long S in mainstream English printing. Once The Times adopted the short “s” exclusively, other publishers followed suit, leading to the rapid disappearance of the long S from English print materials.

This shift had direct implications for the word “Atheiſt”. By the early 19th century, as English printers fully transitioned to using the short “s,” the spelling “Atheiſt” naturally became “Atheist”. This change was not a deliberate alteration of meaning but a byproduct of broader typographical reforms that aimed to improve the readability and uniformity of English texts. Additionally, the rise of modern dictionaries reinforced this transition. Samuel Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary of the English Language still included words printed with the long S, but by the early 19th century, lexicographers such as Noah Webster had adopted the short “s” as the universal standard. This ensured that all future English publications, including dictionaries and encyclopedias, would use “Atheist” in its modern spelling.

This typographical transition is crucial to understanding the history of the word “Atheist”. Claims that “Atheist” appeared in print before the late 18th century are based on misreadings of early texts, where the long S has been mistakenly transcribed by modern historians as a short “s”. The actual transition to the modern spelling occurred gradually, driven by technological and linguistic reforms in the printing industry, which also coincided with a redefinition of the term itself as self-identifying ‘Atheist’ people appeared and formed an organized intellectual movement.

How the Word “Atheist” Evolved from Insult to Identity

Early Modern Period (16th–17th Centuries): A Religious and Political Insult

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the term “Atheiſt” was not a neutral descriptor of religious disbelief but a weaponized insult wielded in theological and political disputes. This period saw the height of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, during which both Catholics and Protestants used “Atheiſt” to discredit rivals rather than to describe individuals who explicitly denied the existence of God.

One of the earliest recorded uses of the word appears in John Martiall’s A Replie to Mr. Calfhill’s Blasphemous Answer (1566). Martiall, a Catholic polemicist, accused Protestant reformers of being “Atheiſts”, suggesting that by rejecting traditional Catholic doctrines, they had abandoned true faith (Martiall pg 162). However, this did not mean they denied the existence of God—rather, it was a rhetorical attack, equating religious nonconformity with godlessness.

Similarly, in 1571, Arthur Golding, an English translator of John Calvin’s Commentaries on the Psalms, used the plural form “Atheiſtes” in reference to morally corrupt individuals who, in Calvinist theology, lived as if God did not exist. Again, the implication was not philosophical disbelief but practical impiety—people whose actions defied Christian morality and authority.

By the 17th century, the word Atheiſt became even more politically charged. In England and France, accusations of atheism were commonly levied against skeptics, deists, and critics of religious institutions. The Jesuit priest François Garasse, in his 1623 work La Doctrine Curieuse des Beaux Esprits, denounced libertines and skeptics as “Atheiſts,” portraying them as threats to social order. Even the philosopher Thomas Hobbes was branded an “Atheiſt” for advocating a materialist and mechanistic view of the universe, despite the fact that Hobbes himself never denied the existence of a Christian God.

Throughout this period, few would self-identify as an Atheiſt or any variation thereof, as doing so could result in imprisonment, execution or exile. Instead, the word was overwhelmingly used as a slur to label political and/or ideological rivals as morally corrupt, irreligious, or politically subversive. Suggesting that the Christian god did not exist was criminalized throughout Europe, such as in England’s Blasphemy Act of 1698, which reinforced the term’s negative connotations, ensuring that Atheiſt remained an accusation rather than a self-identity. As an example of the seriousness of a person actually declaring the Christian God to not exist, on January 8th, 1697 the 20-year old Thomas Aikenhead, a student at University of Edinburgh, was executed for comparing the Old Testament to Aesop’s Fables and suggesting Jesus had been a magician.

Dispelling the Myth that the Meaning of Atheist Was Developed In Opposition to Theist

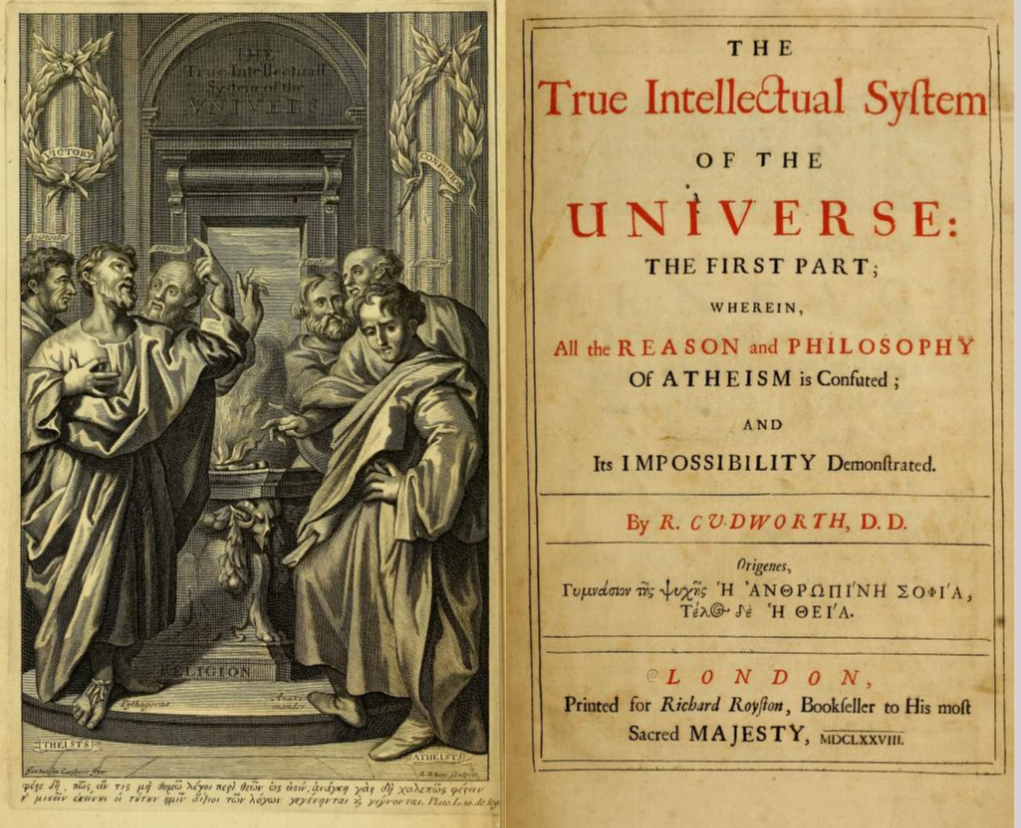

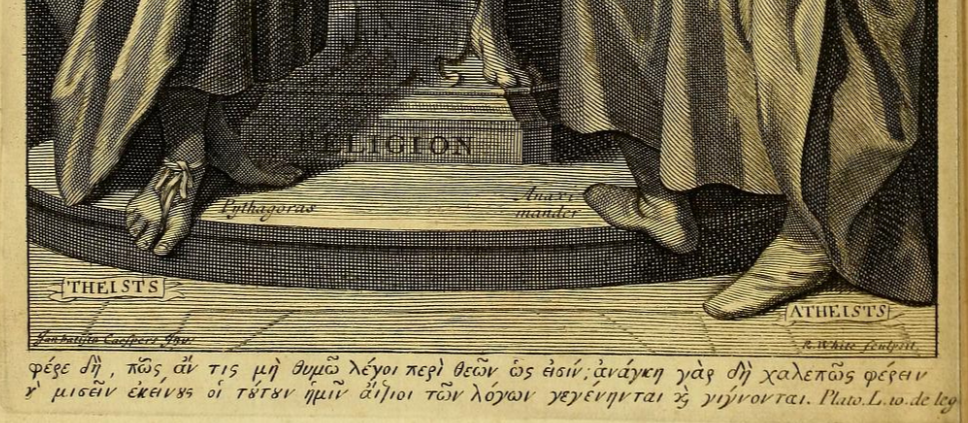

There is one sole outlier I have encountered after reading through hundreds of primary sources from this period that feature the word Atheiſt, and that outlier is the Anglican apologist Ralph Cudworth’s ‘The true intellectual system of the universe ‘(1678). In this work, the engraving image of the title page features a group of Greek philosophers (Aristotle, Pythagoras and Socrates) on the left with a scroll below their feet titled, ‘Theists’ and to the right a depiction of Strato, Epicurus and Anaximander with a scroll at their feet titled ‘Atheists’. The British Museum attributes the engraving to London engraver Robert White (1645-1703) and a copy of this book in the collection of John Adams Library features this engraving.

It must be noted that Cudworth’s book has irregularities, as while the title page spells ‘Atheist’ the rest of the work uses the Long S (ſ), spelling Atheiſt and Atheiſts. As such, the engraving and title page are outliers that might be attributable to the illustration engraver lacking typeset containing the Long S (ſ) character. Regardless, the importance of Cudworth’s text here is not in its early spelling of ‘Atheiſt’ as ‘Atheist’ but in that in this work Cudworth originally coined the term ‘Theists’, spelled as Theiſsts elsewhere in the book (such as page 966 of the facsimile) and contrasted it to Atheiſt.

While the word Theists / Theiſsts is clearly used to contrast with Atheists / Atheiſt, it is important to stress that the book presented Strato of Lampsacus, Epicurus and Anaximander as Atheiſt, and criticized their philosophies as forms of Atheiſt views. In actuality none of these men can rightfully be considered an Atheist in the modern sense of the word, as all evidence indicates these men believed in the existence of deities. Rather, Cudworth labels them as Atheiſt not because they disbelieved in deities but instead because their philosophies were deemed by him to conflict with Anglican theology. Cudworth was therefore using Atheiſt in the same way as all his other contemporaries did, as an insult to those who were theists but disagreed with his version of orthodoxy. It must be further pointed out that Cudworth labeled Aristotle, Pythagoras and Socrates as ‘Theists’ despite the truth that none of these men believed in the Anglican doctrine that Cudworth claimed their viewpoints were aligned with. Cudworth’s book is, in truth, a rather disorganized mess of nonsense when scrutinized for epistemic rigor even by his own definitions.

Another important thing to stress is that the word Theist is also not a Greek word, but instead invented by Cudworth in the late 17th century after the Early Modern English term Atheiſt was already long in use. Cudworth developed the term Theist in response to the discussion of materialistic ideas during his lifetime that were influenced by ancient Greek writers such as Epicurus. Theism, to Cudworth, had the meaning of those ancient Greek writers whose ideas he believed supported his preferred Christian dogmas, and did not have the modern definition people think of today to describe anyone who believed in deities.

Cudworth’s work does, however, appear to have been influential in that it presented a binary of Theist and Atheist in the popular consciousness of its time, which influenced later writers as the term Atheism took on new meaning as an organized intellectual movement.

The re-definition for ‘Theist’ and ‘Theism’ as a broader classification of religions would only come a few hundred years later in 1852 when the British secularist George Holyoake invented the term non-theist for a generalized disbelief in deities. It must be noted this is a term Holyoake coined after he had been charged with blasphemy and imprisoned in 1842. He also coined the term ‘secularism’ around this same time period, and founded the newspaper Secular Review in August 1876.

So upon real historical review, we find that the history of the modern meaning of the terms theism and non-theism come only after the modern meaning of Atheism as a distinct ideological position that rejects a belief in deities. While Cudworth invented the word theism before this time, he did not use it in the same way it has become used by contemporary English speakers today after Holyoake redefined it.

Enlightenment Emergence of Philosophical Atheism as Self-Identification

Among the first individuals to publicly declare themselves Atheists in the modern sense of the word was Matthias Knutzen (1646–1674), a radical German freethinker who, in 1674 distributed pamphlets where he explicitly denied the existence of the Christian God and argued that morality could exist without religion. Though suppressed, his writings were one of the first known instances of someone openly distributing such literature. Importantly, Knutzen claimed he was part of a community of other like minded folks which led to considerable controversy and comment, including German theologian Tobias Pfanner who claimed that Knutzen’s work surpassed the infamy of all enemies of religion known until then.

Pierre Bayle included Knutzen in Vol. II of his Dictionnaire historique et critique (1697) which further popularized him, writing,

“KNUZEN (Mathias), a native of Holstein, reached such a level of extravagance that he publicly founded Atheïlme and undertook long journeys to recruit followers. He was a restless spirit, who began spreading his impieties in Königsberg in Prussia.

He boasted of having a large number of comrades in the main cities of Europe, claiming up to 700 followers in the city of Jena alone. His sect was called the Conscientarians (Tobias Sanctuaires), because he declared that there was no other God, no other Religion, no other legitimate Magistracy than Conscience, which teaches all men the three precepts of Natural Law:

- Do no harm to anyone

- Live honestly

- Give to each person what is due to them

He summarized his doctrine in a rather short letter, of which multiple copies were circulated. It was denounced in Rome. You will find the entire letter in the latest edition of Mihi vitio crædulus.

All of this was refuted in the same language by a Lutheran professor named Johann Musaeus (Jean Musaeus). This small sect began around the year 1673.

The Continuator of Micrælius Crædulus reduced the contents of this letter to six articles:

- There is no God nor Devil.

- The Magistrates are nothing.

- The temples must be destroyed.

- The priests must be rejected.

- The Magistracy must be replaced with the governance of reason.

- Sacred texts should be discarded and in place of priests, there should be knowledge and reason combined with conscience, which teaches to live honorably, harm no one, and give to each what is due.

- That marriage is no different from prostitution.

- That there is only one life, and after this one, neither reward nor punishment is given.

- That the Holy Scriptures contradict themselves.

This system, in addition to the most horrible impiety, clearly contains extravagance, for one must be absolutely mad to believe that humanity could subsist without magistrates. It is true that they would not be necessary if all men followed the precepts of conscience that this impious man articulates; but do they follow them, even in countries where judges punish crimes against one’s neighbor with the utmost severity?

I do not know whether one could not say that there is no folly, however extreme, that does not teach us some truth. The follies of this German show us that the ideas of natural religion, the ideas of honesty, the impressions of reason—in short, the light of conscience—can still remain in a man’s mind, even after the ideas of God’s existence and the law of an afterlife have been erased.“

This social shift of European people openly rejecting belief in the Christian God was solidified by French Enlightenment thinkers, particularly Denis Diderot, editor of the Encyclopédie (published in volumes between 1751 to 1772), who during this time period moved from Deism to outright Atheism, rejecting divine revelation and advocating for a materialist view of the universe. However, it was Paul-Henri Dietrich, Baron d’Holbach‘s Système de la Nature (1770) that fully articulated a systematic Atheistic philosophy. D’Holbach denied the existence of God, rejected religious morality and argued that all phenomena could be explained through natural laws. This publication was deeply influential and popularized the changed meaning of words originating from atheos (such as Atheiſt and Athéisme) to instead take on new meaning, becoming distinctly new words describing disbelief in deities due to the person possessing a naturalism philosophical worldview.

In Britain, David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) further undermined traditional arguments for claims of gods’ existing, using Empirical skepticism to challenge the teleological and cosmological arguments for a divine creator. Though Hume never explicitly identified as an Atheist, his work laid the foundation for secular thought in the following centuries.

The French Revolution (1789–1799) was another critical moment for Atheism. Revolutionary leaders, such as Jacques Hébert and Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette, abolished state-sponsored Christian religion and instituted the Cult of Reason. While these changes were later reversed by later French regimes, the Revolution demonstrated that a government could function without reliance on religious authority, contributing to the shifting of Atheism from a slur lobbied against rival theologians to instead represent a political and ideological stance rejecting belief in Christianity in favor of the emerging naturalistic sciences.

By the end of the 18th century, Atheism had moved from the shadows of accusation to the forefront of intellectual debate, setting the stage for its formal adoption as an identity in the 19th century.

19th Century: The Rise of Scientific Naturalism and Secular Philosophy

The 19th century saw Atheism become a widely recognized intellectual position, shaped by scientific discoveries and secular philosophy.

The publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) had a profound impact on the discourse surrounding Atheism. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection provided a naturalistic explanation for the diversity of life, challenging the argument from design, which had long been used to justify belief in God. By demonstrating that complex biological structures could arise without divine intervention, Darwin’s work further weakened religious explanations of the natural world.

At the same time, philosophers and scientists embraced materialism and secular humanism:

- Ludwig Büchner’s Force and Matter (1855) argued that all phenomena, including human consciousness, could be explained by physical processes, rejecting the need for a spiritual dimension.

- Ernst Haeckel, a biologist and advocate of Darwinism, promoted Monism in Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (The Natural History of Creation, 1868), which denied the distinction between mind and matter.

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous proclamation, “God is dead” in his 1882 book The Gay Science, signaled the collapse of religious authority over moral and philosophical thought, advocating instead for secular human values.

As these ideas gained traction, Atheism was no longer simply the absence of belief in God—it became a comprehensive worldview grounded in scientific naturalism, materialism and reason. The formation of secular organizations, such as the Ethical Union (1896 – it later changed its name to British Humanist Association) further institutionalized Atheism as a legitimate alternative to religious faith.

20th Century: Atheism as an Organized Intellectual Movement

The 20th century saw Atheism evolve into a global movement, driven by scientific progress, secular governance, and political ideology. In democratic nations, the growth of secular humanist movements led to the formation of organizations advocating for separation of church and state and rationalist ethics.

In the United States, the popularization of Atheism as a social movement owes much to Madalyn Murray O’Hair. Best known for her successful federal lawsuit to remove public school prayer from classrooms, O’Hair founded American Atheists in 1963 and positioned it as a counterweight to religious influence in public life. The definition of Atheism used by her organization was published in the first pages of the American Atheist Magazine it operated as periodical, such as the October 1978 issue where Atheism is expressly defined as,

“1. Atheism is the life philosophy (Weltanschauung) of persons who are free from theism. It is predicated on the ancient Greek Philosophy of Materialism.

2. American Atheism may be defined as the mental attitude which unreservedly accepts the supremacy of reason and aims at establishing a system of philosophy and ethics verifiable by experience, independent of all arbitrary assumptions of authority or creeds.

3. The Materialist philosophy declares that the cosmos is devoid of immanent conscious purpose; that it is governed by its own inherent, immutable and impersonal law; that there is no supernatural interference in human life; that man – finding his resources within himself – can and must create his own destiny; and that his potential for good and higher development is for all practical purposes unlimited.“

It is therefore incontestable that the principal organization for the promotion of Atheism in the United States from the mid to late 20th century expressly defined Atheism as intertwined with naturalism, and fundamentally rejected a belief in all supernatural things.

Furthermore, American Atheist Magazine frequently published lectures reprinting and discussing the works of prior 19th century Atheist thinkers such as Robert G. Ingersoll and D.M. Bennet in a series of Roots of Atheism editorials published throughout the 1970s, showing clear lineage to the Atheism of O’Hair and that of the past movement.

By the late 20th century, Atheism entered mainstream public discourse, thanks to public intellectuals such as Carl Sagan, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. The rise of New Atheism in the early 2000s, led by Dawkins, Hitchens, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett, brought Atheistic arguments into popular culture, challenging religious beliefs with scientific reasoning. All of these New Atheist authors promoted naturalism and rejected the existence of the supernatural.

By the 21st century, Atheism was no longer an obscure fringe position but started growing in popularity as an accepted intellectual and cultural stance, marking the culmination of its transformation from an insult to an identity.

The Role of Christian Apologetics in Distorting the History of Atheism

How Apologists Have Misrepresented Atheism’s Origins by Conflating It with Ancient Terms Like Atheos

As mentioned previously at the start of this essay, Christian apologists have deliberately misrepresented the history of Atheism by falsely equating it with the ancient Greek term atheos (ἄθεος). This conflation has been used to argue that Atheism has always existed as a vague form of disbelief, rather than as a distinct modern ideological movement rooted in scientific skepticism and naturalism. However, as we have done earlier, closer examination of historical texts, linguistic development, and scholarly discourse shows that modern Atheism is a uniquely post-Enlightenment phenomenon, not a direct continuation of ancient beliefs.

The Greek word atheos originally meant “without gods” or “godless,” but it did not denote a philosophical rejection of all supernatural claims. Instead, it was primarily used as a pejorative label for individuals who failed to adhere to state-sanctioned religious practices. In classical antiquity, Socrates was accused of being atheos, not because he denied the existence of gods entirely, but because he questioned traditional Athenian deities and introduced new divine concepts (Plato, Apology). Similarly, early Christians were labeled atheoi by the Romans, not because they rejected all gods, but because they refused to worship the Roman pantheon (Justin Martyr, First Apology).

Despite this historical distinction, Christian apologists in the 19th and 20th centuries began falsely equating atheos with the modern English word “Atheist”, in an attempt to retroactively insert modern Atheism into ancient history. This misrepresentation allows apologists to claim that Atheism has always existed as an unstructured, incoherent disbelief, rather than as a defined movement that emerged in the Enlightenment alongside scientific Empiricism.